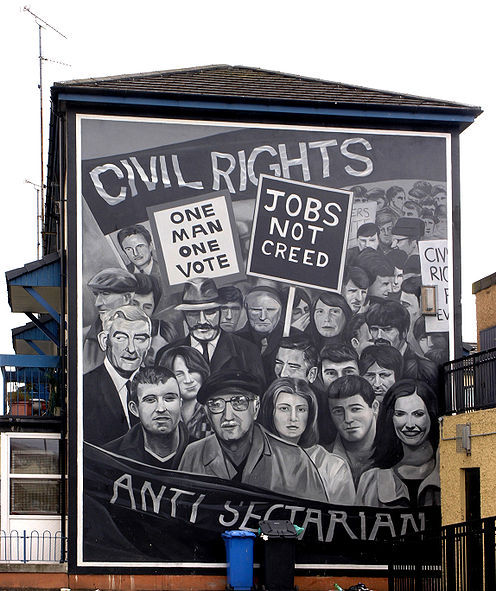

Mural of Civil Rights Campaign in Derry1

Historical Background: Establishment of the Stormont government

The Derry civil rights marches of the late 1960s and early 1970s sought to redress Catholic grievances regarding discrimination, particularly in the areas of housing, voting, and policing. These issues can be traced to the political and security system established under the tenure of Northern Ireland’s first prime minister, James Craig, in the early 1920s.

James Craig2

Under Craig, Northern Ireland's local parliamentary assembly, meeting at Stormont in Belfast, took steps to consolidate Unionist power. It created a police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), which would remain ninety-percent Protestant throughout its existence. It also established a well-armed, all-Protestant paramilitary called the Ulster Special Constabulary, commonly known as the "B Specials." Police were issued a formidable weapon in the form of the Special Powers Act, which allowed arrest without a warrant, internment without a trial, unlimited search powers, and the perogative to ban meetings and publications. Catholics complained that this reduced policing to a form of intimidation, and gave it a military character.3

Northern Ireland's voting system was deliberately manipulated to the advantage of the Unionists. Craig abolished proportional representation, and introduced a first-past-the-post, or winner-takes-all, system. This contrived to keep as few nationalists from winning governmental seats as possible. To further this end, Craig also redrew the local government boundaries along partisan lines. The combination of these two strategies reduced the control of the nationalists from twenty-four councils to thirteen. The voting system was so biased towards the Unionists, that in Derry, ten thousand nationalist voters elected eight councillors while seventy-five hundred Unionists elected twelve. This clear imbalance caused deep resentment in Catholic voters. A senior member of the Unionist Party said:

“If ever a community had a right to demonstrate against the denial of civil rights, Derry is the finest example. A Roman Catholic and nationalist city has for three or four decades been administered (and none too fairly administered) by a Protestant and Unionist majority secured by a manipulation of the ward boundaries for the sole purpose of retaining Unionist control. I was consulted by Sir James Craig at the time it was done. Craig thought that the fate of our constitution was on a knife-edge at the time and that, in the circumstances, it was defensible on the basis that the safety of the State is the supreme law. It was most clearly understood that the arrangement was to be a temporary measure—five years was mentioned.”4

James Craig also introduced a decidedly sectarian flavor to the Stormont government:

“I have always said I am an Orangeman first and a politician and member of this parliament afterwards. All I boast is that we are a Protestant parliament and Protestant state.”5

—Sir James Craig

This attitude would lay the foundation for many forms of discrimination against Catholics. Two of the most concerning were housing allocation discrimination and employment discrimination. Housing was controlled by the local councils, and the local councils were controlled by the Protestants, leaving many Catholics with inadequate or substandard housing. The rate of Catholic unemployment was usually double that of Protestant unemployment. Despite the more conciliatory tone offered by Terence O'Neill, elected prime minister of Northern Ireland in 1963, Catholics experienced little meaningful progress.

Immediate Background: The Formation of the Irish Civil Rights Movement

The first formal manifestation of the growing interest of Irish nationalists in the civil rights movement came in 1967, with the formation of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). Several events during the sixties, both internal and external, contributed to the emergence of this organization. The 1947 Education Act allowed for the growth of an educated Catholic middle class, which was intrigued by the idea of civil rights and found itself in leadership positions in anti-Unionist communities by the 1960s. By the mid-1960s, nationalists were losing faith rapidly that the seemingly well-intentioned O’Neill government could ever adequately address issues in voting, housing, and employment. In 1964, the United Kingdom elected a Labour Party government to its Parliament at Westminster. Nationalist leaders, optimistic that a civil rights campaign had a chance, created the Campaign for Social Justice. The civil rights movement in the United States, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., caught the interest of many nationalists. The NICRA was subsequently born out of the Campaign for Social Justice and a loose alliance of other anti-Unionist groups.6

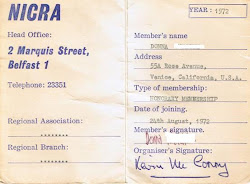

NICRA membership card7

NICRA was an important step in the evolution of the struggle of Northern Ireland because it managed to unite Republicans, nationalists, and other anti-Unionists into one group with one goal. Of course, each of the groups also pursued their own agenda apart from the civil rights movement, and sometimes even within it. While the leadership from NICRA did offer some general direction, many people particpated in the civil rights movement without belonging to any specific association. NICRA was an important, but loose, alliance.8

NICRA did come up with a common list of demands for the O’Neill government. The most important demand for all involved was the insistence on a one-man, one-vote system. The current voting system allowed only home-owners to vote, which excluded about 25% of voters from council and Stormont elections. This system disenfranchised mostly Catholics and helped to keep the Unionist majority in political bodies, even in areas where Unionists did not have a numerical majority. The implementation of the one-man, one-vote system would return Counties Tyrone and Fermanagh and the City of Derry to nationalist control, an event that Unionists would fight hard to prevent. Other NICRA demands included the redrawing of electoral boundaries, anti-discrimination legislation, a points system for housing allocation, the repeal of the Special Powers Act, and the disbanding of the B specials.9

Involvement in the civil rights movement did offer some Positive impact on participants Involvement in a nonviolent struggle tends to lessen submissiveness in participants. They also gain confidence as they take part in something which teaches them their own power in the face of authority. Civil rights training helped participants to overcome their fear; they no longer allowed the establishment to terrorize them. Lastly, it increases the self-esteem of all involved.10

The First Publicity: Austin Currie and the First Civil Rights March

One goal of the civil rights movement was to attract the attention of the press and publicise the cause of civil rights in Northern Ireland. The first incident which sparked media interest and received attention worldwide was to be over housing allocation discrimination.

In the village of Caledon in County Tyrone, housing was controlled by the local Council, just as it was everywhere else in Northern Ireland. While this particular council was well-known for discrimination against Catholics, it was soon to be famous for its policies. In 1968, a Unionist Councillor allocated a house to a nineteen-year-old Protestant girl, passing over two Catholic families. The Protestant girl was secretary to the Councillor's solicitor; the Catholic families had been waiting for a house for two years. It seemed to be a clear-cut case of religion taking precedence over housing need.

Austin Currie was the local MP for the area. He took the case to to the local council, and then to Stormont. He was unsuccessful. So he symbolically occupied the house in dispute. His eviction by the RUC was covered on television.11

Austin Currie12

The incident became the image of the civil rights movement in Ireland, and the publicity generated by the event attracted many more nationalists to the cause. Thousands of people attended a rally held by Currie a few days later. The first civil rights march in Northern Ireland sprang from the support caused by this incident. This incident served to get the word out about the civil rights movement. This means getting the media to cover events, so that the information can reach large numbers of people quickly.13 That same year, the march was held from Coalisland to Dungannon. Thousands of members of the UPV gathered to harass the marchers. Conflict was avoided this time, but the next civil rights march would not be so lucky.14

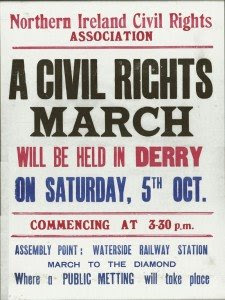

The Fifth of October, 1968

According to McKittrick and McVea, the organizers of the 5 October march were trying to provoke a violent reaction out of the authorities. The goal of their nonviolence was to give the violence-prone an excuse. They knew that if the world could see the establishment in Northern Ireland using violence against peaceful protesters, the fallout would be enormous, and advantageous for the civil rights movement: "the initial and continued nonviolence in the face of a violent response undercuts the perceived justifiability of the violence."16 They hoped to utilize the effects of nonviolence on observers This concept recognizes the importance of observers to nonviolent campaigns: "those people who are violent are more disconcerted when onlookers disapprove." It also recognizes how nonviolent movements benefit greatly from media attention.17

Civil Rights Leaders carry a banner through the Bogside18

They succeeded in riling the authorities: William Craig, the Minister for Home Affairs, banned the march. This onliy increased the number of people attending. Then the RUC spectacularly overreacted, with two Labour MPs and a Dublin cameraman as a witness for the world. The RUC employed water cannons and batons on the peaceful march. Hospitols reported treating seventy-two wounded, among them prominent figure Gerry Fitt.

"A sergeant grabbed me and pulled my coat down over my shoulders to prevent me raising my arms. Two other policemen held me as I was batoned on the head. I could feel blood coursing down my neck and onto my shirt. As I fell to my knees I was roughly grabbed and thown into a police van. At the police station I was shown into a room with a filthy wash basin and told to clean up but I was not interested in that. I wanted the outside world to see the blood still strongly flowing down my face."

—Gerry Fitt

Although O'Neill as Prime Minister was willing to make concessions, other members of his government were quite unapologetic.

"I thought the way the police acted on the day was fair enough. I would have intensified it. I wouldn't have given two hoots for the Labour MPs present, or the TV pictures."

—William Craig19

Video footage of the 5 October civil rights march can be found here.

Part of a documentary which includes interviews with participants of the march as well as video footage of the march can be found here.

The fallout from the 5 Ocober march was indeed widespread and intense. It attracted a worldwide audience and brought international attention to the struggle in Northern Ireland. It generated widespread anger in the Catholic community in Northern Ireland. As a result, the civil rights movement gained public support and activists that were content to remain silent before the events on 5 October.

The events on 5 October sparked numerous sit-ins, protests, and marches all across Northern Ireland.20

Burntollet Bridge

A civil rights group called the People's Democrary (PD) was frustrated by the slowness with which the O'Neill government was addressing civil rights issues. They organized a march from Belfast to Londonderry, even though the proposed route was to take the march through heavily Loyalist areas.

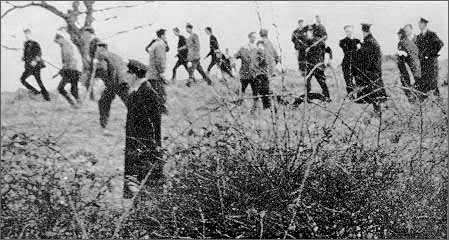

The march was harassed by thousands of Loyalists urged on by Paisleyite Ronald Bunting. But it broke into open violence at Burntollet Bridge, in rural County Derry. A number of Loyalists ambushed the marchers, wielding stones, glass bottles, hatchets, staffs, and other weapons.22 The police were accused of standing by and letting it happen, and even of helping to organize it. In fact, a number of off-duty B-Specials were in the attacking crowd.23

Police mingling with the attackers24

Prior to Burntollet Bridge, the march was criticized by civil rights leaders as foolish, irresponsible, and dangerous. However, after the atrocities at Burntollet Bridge, the PD marchers had the support fo the entire Catholic community.25

"I saw people, including one man who was standing with an armful of stones against his chest on the lower ground to the left of the field. Suddenly, I heard screams coming from behind, and looking around saw a shower of stones in the air. The march scattered in some panic; then I saw a girl being put onto a police tender with blood pouring from her head. Then I saw a television cameraman with blood streaming down his face."

—John Gilmore, Belfast student

The attackers even pursued the injured being transported to the hospitol:

"About fifty yards ahead a group of men armed with sticks and bars formed a road block. One carried a hatchet, another a billhook. For a few minutes it seemed that they were going to drag us from the ambulance. But then the leader contented himself by saying, you got a lot less than you deserved. Next time we see you, it will be the last rites, as you call them, that you'll need. We'll kill each last one of you that turns up in this area again'."26

1970: Civil Rights eclipsed by SDLP

By 1970, the civil rights movement had lost a great deal of its initial momentum. Part of this was due to a phenomenon known as Burnout The Psychology of Peace describes burnout as a condition that happens when "people get very involved and get overwhelmed; too much is asked of them and too little is given to them."27 At this point the civil rights movement had encountered stiff resistance from the RUC and the British authorities. While the movement had received good press, little had been gained in actual concessions. People who had been hopeful and eager to participate in marches were losing heart. The lack of reaction from the government was discouraging more and more supporters. The Burnout phenomenon was cemented by something psychologists call Operant Conditioning. Operant conditioning is the idea that people will repeat an action that is rewarded, but will stop doing something that is punished. The civil rights marchers were not receiving any rewards in the form of concessions from the government, and they were also being punished at times by the RUC and British Army. These factors combined to lessen the enthusiasm for the civil rights movement.

The lack of willing participants in the movement was compounded by a surge in support for the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP). Under the leadership of Gerry Fitt and John Hume, this new voice for nationalists began eclipsing the civil rights movement. The SDLP became the principal voice for nationalism, and remained the largest nationalist party throughout the course of the Troubles.28

Although the civil rights movement had lost its original momentum, the biggest tragedy of the civil rights movement had yet to occur. January 30, 1972 became known as "Bloody Sunday" because of the extensive losses suffered by the marchers.

Bloody Sunday

There are, of course, many differing accounts of what happened on the day known as Bloody Sunday. What is known for sure is this:

- There was an illegal civil rights march organized by NICRA, held in Derry on January 30, 1972 which 10,000-20,000 people attended

- There was a rally at the Free Derry Corner to protest internment without trial

- The regiment of British Paratroopers in the city opened fire on the crowd, firing from 4:10PM until 4:40 PM

- Fourteen marchers died, and twelve were injured

- No soldiers were killed or injured

- No weapons belonging to marchers were ever recovered

The Paratroopers claim that the marchers were armed, dangerous, and a threat to the safety of the city. They say they were attacked with nailbombs and guns.30 This justification shows the impact of nonviolence on the attackers It is a clear-cut example of the self-serving bias, when those using violence attribute their violence to external factors. In order to view themselves favorably, the Paratroopers had to justify their violence, so they placed the blame on the peaceful marchers by labeling them dangerous.31 The Lord Chief Justice, Lord Widgery, released the report of the inquiry into Bloody Sunday which exonerates the Paratroopers. However, this report has been accused of being a "whitewash" and a "cover-up," especially since many of the injured were not called to give testimony. Prime Minister Tony Blair ordered another inquiry into the events of Bloody Sunday in 1998.32

The statements given by local residents and participants in the march flatly contradict the version of events given by the paratroopers. Eyewitnesses claim the troopers opened fire without justification. Even the contested Lord Widgery report states:

"None of the deceased or wounded is proved to have been shot whilst handling a firearm or bomb."33

Witnesses also report that those killed or wounded were unarmed. Furthermore, witnesses have testified that many of those killed were shot in dubious circumstances:

- Patrick Doherty was shot while trying to crawl to safety.

- Kevin McElhinney was also shot while trying to crawl to safety.

- Barney MacGuigan was waving a white handerchief as he left safety to aid Patrick Doherty when he was shot.

- William Nash was also shot while attempting to aid someone.

- James Wray was shot and wounded, and then shot dead at close range while attempting to get to safety.

- Gerald McKinney was shot with both his arms in the air, calling "Don't shoot! Don't shoot!"

- William McKinney was shot when he left cover to assist Gerald McKinney.34

The effects of Bloody Sunday, both within Northern Ireland and internationally, were far-reaching. Within Northern Ireland, the deaths of fourteen protestors generated a wave of intense anger. There was a huge increase in nationalist isolation— the Catholics who hadn't yet, withdrew from public life. Resentment towards the British intensified. According to Father Daly, who became the Bishop of Derry, "A lot of the younger people in Derry who might have been more pacifist became quite militant as a result of [Bloody Sunday]." IRA recruitment skyrocketed. The Republic of Ireland held a national day of mourning and recalled its ambassador from London. After days of protests, an angry mob burned down the British Embassy in Dublin. The incident also sparked worldwide indignation.35

The Song Go on Home, British Soldiers reflects the anger of the Catholic communities after Bloody Sunday.

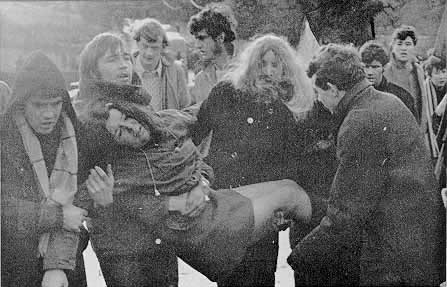

Marchers flee from the Paratroopers.37

Marchers carry a fallen comrade38

Link to a site with great photographs taken during the Bogside Riots in Derry

Fred Hoare Photography